Dronestrike data organized, visualized, and analyzed.

This page explores our research questions through a series of data visualizations.

In this section, we cover the following topics:

Drone, in warfare discourse, refers to unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs. These are remote-controlled and give operators what is often referred to as "drone vision" through camera attachments capturing live video feed.

These machines have been used for many things, including espionage, parcel delivery, and of course, military operations.

Targets of drone strikes include leaders, local commanders and operatives of al-Qaeda, Afghani and Pakistani Taliban, and networks carrying out attacks on NATO forces in Afghanistan.[1]

When we speak about military drone operations, there are two kinds:

These are authorized by the president in a form of executive execution. The targets have not been indicted for a crime, let alone convicted, and have been identified as enemy combatants through an opaque process.

This type of targeting allows for wider parameters, quicker response and authorization at a lower command level. They are based on categories of possible target groups and patterns of movement rather than on identified individuals.[2]

The databases provided by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism demonstrate that drones characterize contemporary warfare. Why are drones used over conventional boots-on-the-ground tactics? There are many arguments defending the use of drones, but here are the main "benefits":

Drones are cheaper to produce and can stay airborne much longer than conventional aircrafts. No physical pilot means less money spent on personnel and their training, avoids loss of time, & saves fuel.

Drones can "go places troops can't" & eliminate the possibility of American military deaths. Furthermore, drones make it easier for the U.S. to conduct operations from military bases in supporting nations.

Policy writing can't catch up to the speed at which UAVs are developed, meaning responsibility over drone operations can be given to anyone & be enacted at great speed with little-to-no legal consequences.[3]

Our research examines the relationship between the past three United States presidential administrations and their use of drone warfare in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia.

Using drone strike data from The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, we are identifying whether there are spatial, temporal, and empirical shifts in the drone campaigns conducted by the different presidential administrations.

The data set begins with the first drone-enabled airstrike in Yemen in 2002 (Despite the first drone-enabled airstrike ever happened in Afghanistan in 2001; read more about this in our Data Critique) and continues into the present, with the Bureau of Investigative Journalism updating the dataset as needed to include drone strikes authorized by the Trump administration.

To answer our research question, we found that there were three key areas of the data we needed to explore in detail:

GEOTEMPORAL POLITICS

Because military drone strikes are both covert and deployed remotely, the geographies of war and international intervention have become increasingly complex. International laws and international human rights laws (IHRL) have attempted to create legal paradigms restricting drone strikes. The key legal frameworks to consider are that strikes should be

The US’s interpretations of international laws have shifted across presidential administrations, impacting the geography of drone warfare.[5] The US invasion of Afghanistan created battlegrounds of armed conflict that legitimized the use of drones and in 2006, President Bush received support from Pakistani President Perves Musharraf that gave consent to US airstrikes against Al-Qaeda targets.[6]

The scope of US drone warfare under President Obama expanded not only in its development and technology, but also its territoriality. The governments of Somalia and Yemen approved US military support and drone strikes, justifying the geographical expansion of drone strike areas in the respective nations.[7] Later, though, the legitimacy of US drone strikes would become convoluted as Pakistan publicly withdrew consent and Yemen’s president was ousted by Houthi rebels.[8]

Drone strikes on Pakistan, Somalia, Yemen, and Afghanistan still continued, often sidestepping international laws. However, concern over the drone program also led to President Obama tightening standards for drone strikes and instituting safeguards against civilian casualties, in effect limiting geographical expansion.[9]

Although the Trump administration is only halfway through its first term at the time of this project, the shifts in its policies already have major implications for the geography of US drone warfare. In the first year of his presidency, Donald Trump expanded warzones within Yemen and Somalia by designating an increasing amount of provinces as “areas of active hostility,” allowing the US military to launch drone strikes against these regions without having to go through presidential vetting or approval.[10] President Trump also rolled back Obama’s restrictions on drone strike targets and protections against civilian deaths, further expanding the capacity of the drone program.[11]

Journalism is central to the diffusion of information regarding the US drone campaign abroad, making it a key source for data and documentation. The datasets from The Bureau of Investigative Journalism use both Western and non-Western news sources in order to quantify strikes and their aftermath (deaths, injuries, etc.). Journalism is also the only documentation we have other than what the White House has publicly admitted to.

This does, however, come with some problems as there would naturally be discrepancies over what various news sources deem to be the truth. These discrepancies influence the way data is represented. For example, death and injury counts are shown as ranges rather than concrete numbers since different sources may report different figures.

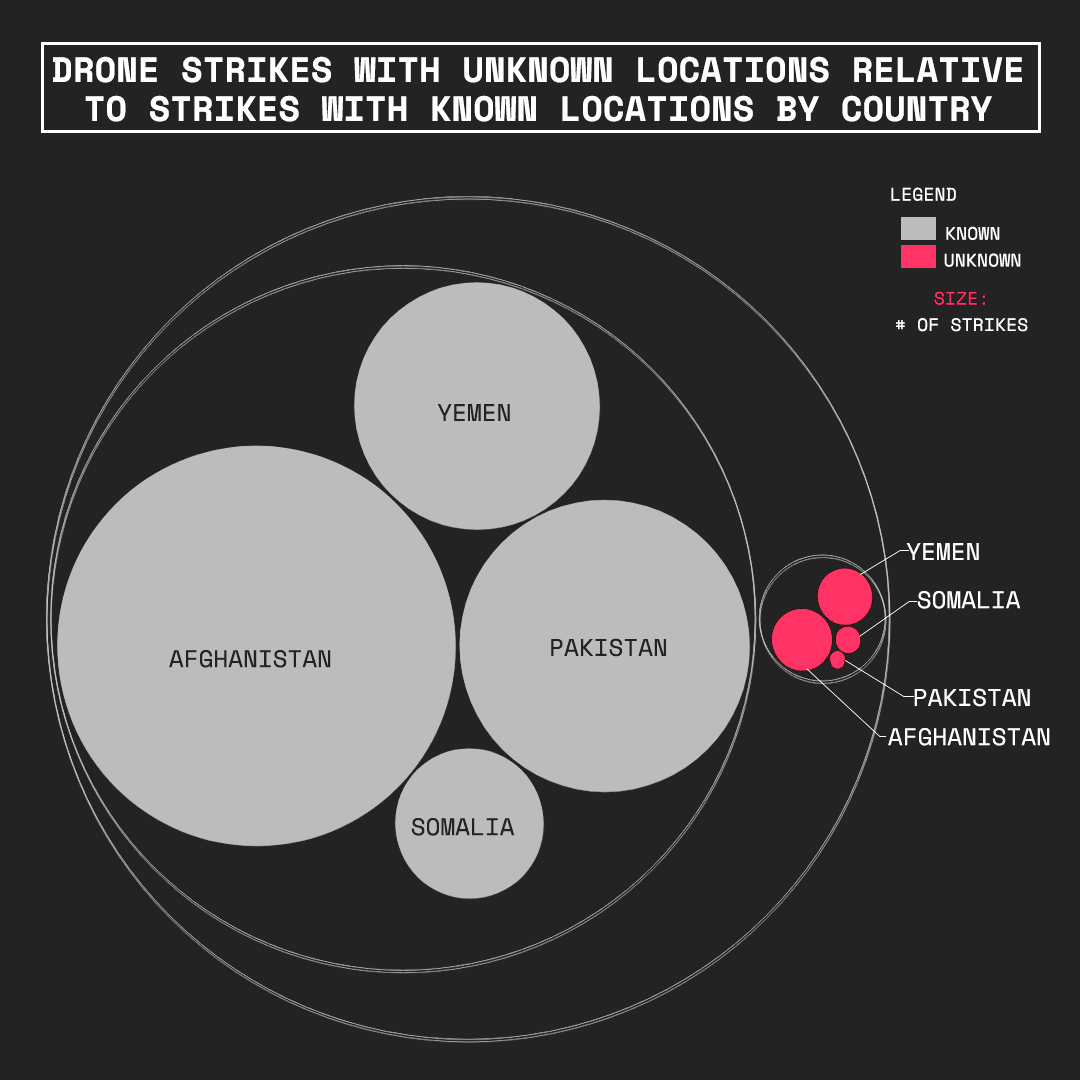

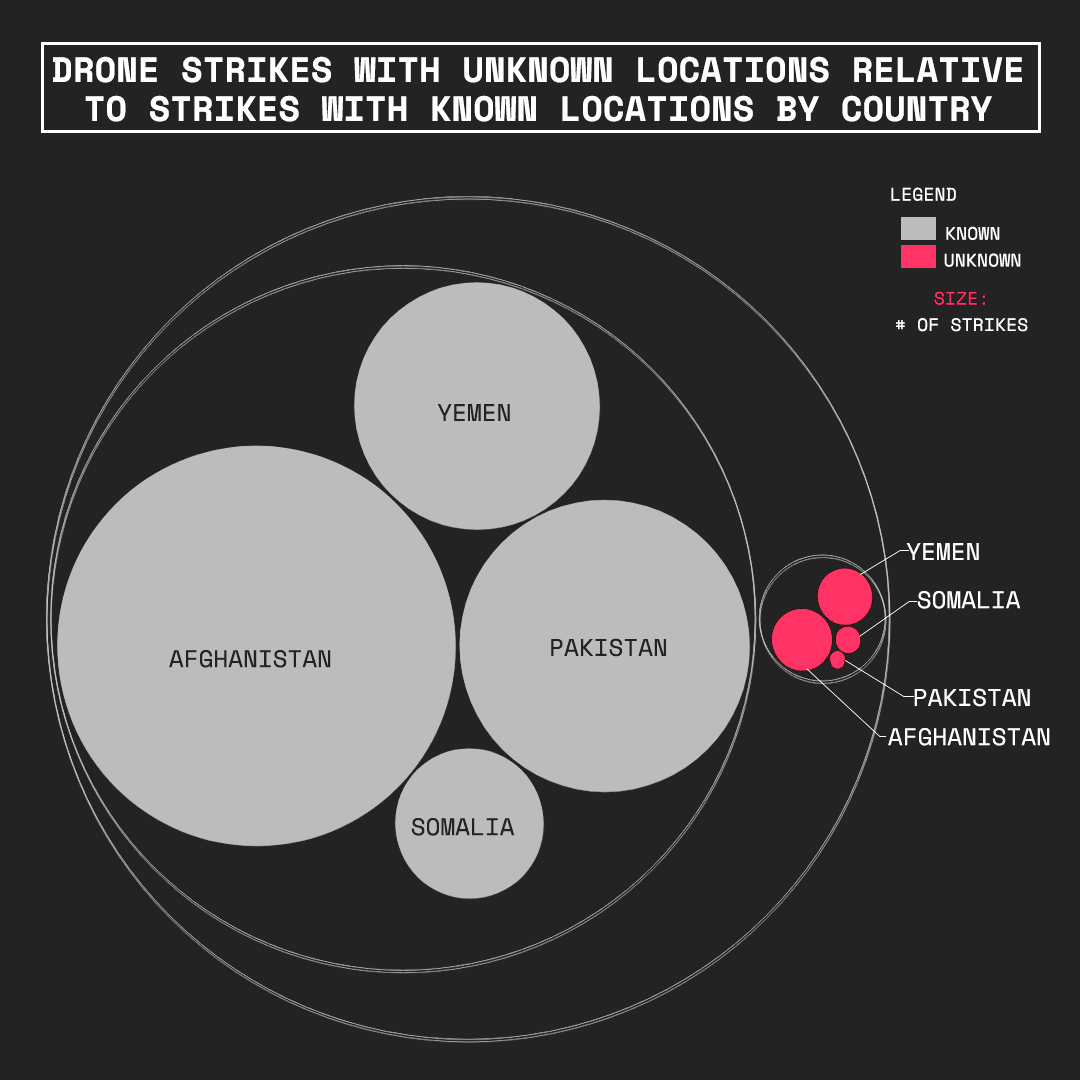

Discrepancies in reporting also account for why some of the reported strikes are listed as having unknown locations, since some reports may have contradictory listings.

Proportionally, strikes with unknown locations are a minority. However, they may also represent strikes that were undercovered by news media, making their location unknown due to a lack of attention. Data absence is not always representative of bad or false data; data absence, in itself, can say a lot about which strikes, villages, or demographics were deemed important enough for coverage and which ones were considered too insignificant to be addressed.

Because drone strikes have significant social and political impacts, it is critical to have structures and mechanisms that enforce transparency and accountability in data reporting. Due to the covert and military nature of drone strikes, this is easier said than done.

According to the Geneva Convention military forces should be used with:

Despite a few flaws and lies, the US government attempted to maintain a sense of transparency by consistently releasing information during the Cold War and Vietnam to avoid scrutiny. However, the Obama administration has kept drone activity out of congress, courts, and media. It has taken them many years to both acknowledge and release limited information about the drones programme, such as confirming the countries where drones are present.

The drones programme has two branches, those being:

The JSOC programme conforms to military rules and standards for target selection, review, and command chain accountability.

The CIA is entirely classified. It has released almost no data and is not clear about who is involved in selecting targets, in the chain of command, and held accountable for violating war laws.

From a policy standpoint, the drone programme has received similar treatment to covert and spy operations in terms of standards for accountability and transparency. This allows information to be kept within the executive branch and intelligence committees, instead of congress, courts, and the general public. However, this is a form of spying which has caused the loss of many lives and counters previous domestic and current global trends of warfare.[12]

It is incredibly difficult to identify the source of a drone strike from the ground. One of the most interesting aspects about the Afghanistan and Somalia datasets is that they include data on which strikes were confirmed and unconfirmed by government or journalistic sources.

This area graph shows the number of strikes that are listed as confirmed (confirmation must come from a US government source, named international sources, or by three local sources) in proportion to those that are listed as unconfirmed.

Lack of confirmation can be attributed to discrepancies in journalistic reporting as well as the influences of political actors. As previously stated, a lack of confirmation may mean that certain strikes were undercovered or ignored by news media. In other cases, the lack of confirmation may reflect the politicization of news reporting. For example, a study on civilian tolls in Pakistan showed that the media in Taliban-controlled regions often use reports on drone strikes to propagate anti-US sentiment.[13] Reported figures may or may not be hyperbolized as part of political agendas.

This is not to say that there is no fault on behalf of the US; in fact, the same study criticizes the US’s lack of transparency as a key reason for why there is so much ambiguity over data reporting.[14] Attention should also be given to the spikes in strike confirmations, which may reflect changing political ambitions. While the drone programme under the Obama administration was known for its secrecy, President Trump has been outspoken about his intentions to accelerate the programme since his campaign.[15] Confirmations, then, may be an intentional means of spotlighting and projecting US hegemony.

Improvements in CIA targeting procedures and spy networks and technology reflect tactical choices that have led to sustainable improvements in accuracy. The CIA has demonstrated increased awareness, caution, and restraint in protecting civilian lives by passing up certain attack opportunities. Technology improvements, such as the addition of homing beacons, smaller and more precise missiles, and longer battery life which allows for more patient surveillance.[16]

Drone operators often misidentify non-combatant civilians as a result of three factors: misjudgment, misinformation, and inaccurate reporting in drone strikes. Technological limitations in video surveillance and failures in data transport can restrict the operator’s field of view and mistaken a civilian for a target.[17]

The Obama administration broadly interpreted the Authorization to Use Military Force (AUMF), using it to back a maximum discretion policy in pursuing terrorists. This widened the definition of:

widened the scope of relationship to al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or their affiliates.

geographic region widened to any place the US determines a growing threat with lack of evidence of local government ability of control, including any place terrorists may be present and planning attacks).

asserted the right of anticipatory self-defense, in which drone strikes can be not only defensive but also preventative with minimal evidence for necessity of action and drone strikes as the optimal attack option.

This shift in interpretation has enabled strikes against targets that are indirectly related to the original combatants.[18]

The designation of combatant status is more complex, as many targets are irregular fighters who do not dress or self identify as combatants. In fact, blending into the civilian population is a common strategy for protection.[19] Because military operations and attacks must avoid “incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof,” drone strikes against combatants pose many ethical, legal, and political complications. Limited availability of drone strike information makes it difficult to calculate whether or not individual operations violate international protections against risks of civilian casualties.[20] Additionally, both the Obama and Trump administrations have called civilian casualties inevitable and unavoidable.[21]

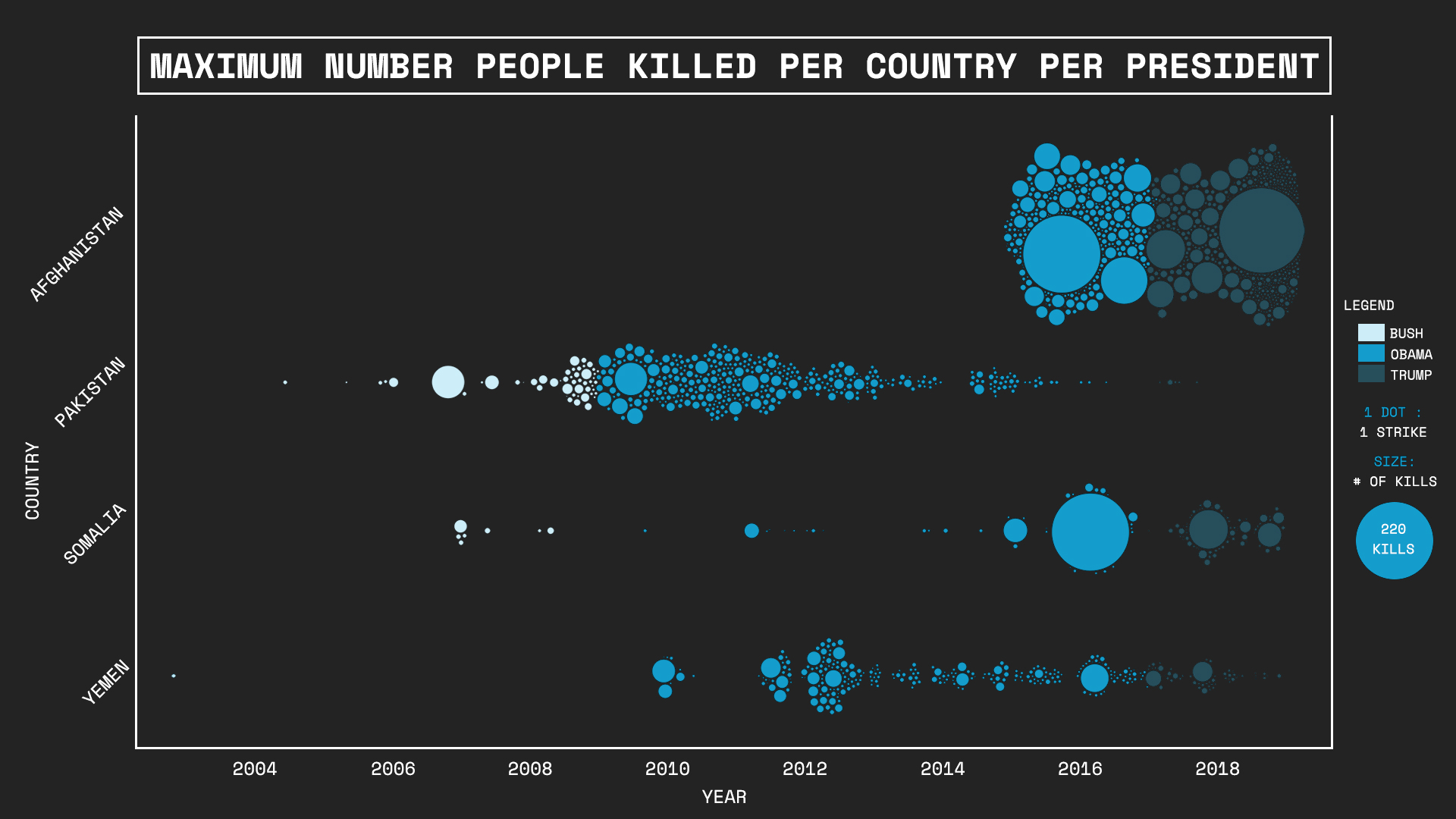

In this graph we can see the difference in the number, frequency, and maximum casualties per strike by country over time. It is important to note that this graph does not include strikes that did not include specific strike locations. We discuss this and other data absences in this data visualization, which represents the strikes with unknown locations relative to strikes with known locations.

From September to December 2018, the Trump administration has been especially targeting Afghanistan in terms of frequency of strike and death rate per strike. Relative to the three other countries, Afghanistan has received the most casualties per strike as signaled by the 2 largest dots in that group. These largest dots represent 220 kills, which is the greatest amount of casualties for any of the strikes. This intensification of attacks might be attributed to Trump’s proclivity to political controversy and his anti-Islam stance.[22] The figures only support that claim as the frequency and intensity of drone strikes continues to increase dramatically within the current administration.

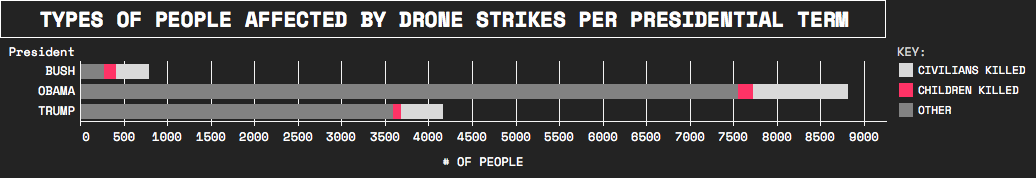

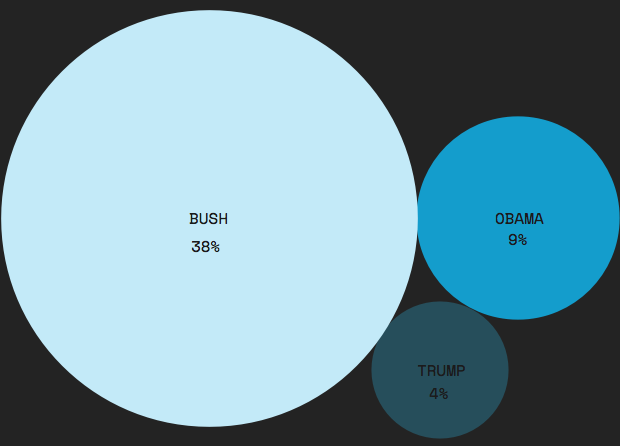

It is important to keep in mind that while Bush's and Obama's full presidential terms are represented, only the first two years of Trump's term appear in this graph. While Obama was responsible for the most civilian and children deaths overall, this graph represents his entire 8-year term. If Trump continues on his trajectory of deaths and has a 8-year term, he is projected to kill nearly double as many civilians and children total as Obama did. This can be attributed to how Obama issued the Presidential Policy Guidance, which tightened procedures for use of drone strikes including standards that targets must be “a continuing, imminent threat to Americans” and a “near certainty” that there would be no civilian casualties in 2013.[23] Trump, however, began to dismantle these guidelines, including the high-level vetting of proposed drone strikes, the limitation to only targeting “continuing and imminent threats,” and protections against civilian deaths in 2017.[24] This change and shift of prioritization between the presidents may reveal why there is still a significant number of civilian deaths during Trump’s two years in office.

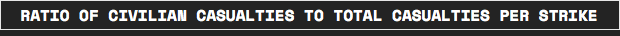

At the same time, however, assessing the average accuracy of individual drone strikes reveals a different aspect of the data. The average percentage of civilians killed per strike for Bush, Obama, and Trump's terms are 0.38, 0.09, and 0.04 respectively. Since the percentage of average civilians killed per strike has reduced from 38% to 4% between Bush and Trump’s years in office, this could be an indication that either intelligence has bettered on target location or that technology has improved within the past few decades. Combining information from both graphs and the background of Trump’s approach towards civilian deaths, it seems as though a combination of Obama’s emphasis on reducing civilian deaths (bringing the percentage down from 38% to 9%) and increased intelligence and technology over the year might be attributable to this difference.

Another explanation could be the removal of Obama’s guideline that a target must be a “continuing and imminent threat.” Without this guideline, the justifications for drone strike targets are looser. This may mean that individuals who would have counted as civilians under Obama’s standards might now be considered as targets and would no longer be listed under the civilian category.

This graph reveals that as time progressed, strikes in the different countries fluctuated. Drone strikes in Pakistan were especially prevalent during Obama’s administration, and a focus on Afghanistan has remained since Trump took office. This may be attributable to how Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif withdrew consent to US drone strikes on Pakistan, condemning the strikes as a “violation of Pakistan’s sovereignty and territorial integrity” in 2013.[25] Additionally, while it may seem as though Obama has killed more total people overall, if Trump has an 8 year term, he is projected to kill nearly double as many people total as Obama did. Thus, while Trump may be killing an increased number of targeted individuals, it is questionable about whether killing this massive number of people is ethical.

There have been some efforts to provide condolence payments to strike victims and their parents, however the payments vary by region and do not represent a just restitution of rights. Despite no official acknowledgement of strike victims, the US military provided condolence payments to Afghanistan from 2005 to 2014. However, the monetary compensation was significantly lower compared to payments to other countries. For example, Yemeni families of two drone victims received over $155,000 while an Afghan family only received $2000. In other cases, victims and their families do not receive any compensation whatsoever.[26]

CONCLUSIONS

[1] Plaw, Avery, et al. "Practice Makes Perfect?: The Changing Civilian Toll of CIA Drone Strikes in Pakistan." Perspectives on Terrorism, Dec. 2011, pp. 51–69., doi:10.21236/ada599423.

[2] Byrne, Max. "Consent and the Use of Force: an Examination of ‘Intervention by Invitation’ as a Basis for US Drone Strikes in Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen." Journal on the Use of Force and International Law, vol. 3, no. 1, Feb. 2016, pp. 97–125., doi:10.1080/20531702.2015.1135658.

[3] Byrne, Max. "Consent and the Use of Force: an Examination of ‘Intervention by Invitation’ as a Basis for US Drone Strikes in Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen." Journal on the Use of Force and International Law, vol. 3, no. 1, Feb. 2016, pp. 97–125., doi:10.1080/20531702.2015.1135658.; Byrne, Max. "Drone Use ‘Outside Areas of Active Hostilities’: An Examination of the Legal Paradigms Governing US Covert Remote Strikes." Netherlands International Law Review, vol. 64, no. 1, 2017, pp. 3–41., doi:10.1007/s40802-017-0078-1.

[4] Boyle, Michael J. "The Legal and Ethical Implications of Drone Warfare." Legal and Ethical Implications of Drone Warfare, 2015, pp. 1–22., doi:10.4324/9781315473451-1.

[5] Miller, Greg. "Yemeni President Acknowledges Approving U.S. Drone Strikes." The Washington Post, WP Company, 29 Sept. 2012, www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/yemeni-president-acknowledges-approving-us-drone-strikes/2012/09/29/09bec2ae-0a56-11e2-afff-d6c7f20a83bf_story.html.

[6] Lewis, Michael W. "Guest Post: Pakistan's Official Withdrawal of Consent for Drone Strikes." Opinio Juris, 10 June 2013, https://opiniojuris.org/2013/06/10/guest-post-pakistans-official-withdrawal-of-consent-for-drone-strikes/.

[7] "Procedures for Approving Direct Action Against Terrorist Targets Located Outside the United States and Areas of Active Hostilities." 22 May 2013, www.documentcloud.org/documents/3006440-Presidential-Policy-Guidance-May-2013-Targeted.html.

[8] Kube, Courtney, et al. "U.S. Airstrikes against Yemen Terror Groups Grew Sixfold under Trump." NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 1 Feb. 2018, www.nbcnews.com/news/mideast/u-s-airstrikes-yemen-have-increased-sixfold-under-trump-n843886.

[9] Savage, Charlie, and Eric Schmitt. "Trump Poised to Drop Some Limits on Drone Strikes and Commando Raids." The New York Times, The New York Times, 21 Sept. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/09/21/us/politics/trump-drone-strikes-commando-raids-rules.html.

[10] Boyle, Michael J. "The Legal and Ethical Implications of Drone Warfare." Legal and Ethical Implications of Drone Warfare, 2015, pp. 1–22., doi:10.4324/9781315473451-1.

[11] Plaw, Avery, et al. "Practice Makes Perfect?: The Changing Civilian Toll of CIA Drone Strikes in Pakistan." Perspectives on Terrorism, Dec. 2011, pp. 51–69., doi:10.21236/ada599423.

[12] Plaw, Fricker, and Williams, 64–65.

[13] Ken Dilanian and Courtney Kube, "Trump Administration Wants to Increase CIA Drone Strikes," NBC News, September 18, 2017, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/military/trump-admin-wants-increase-cia-drone-strikes-n802311.

[14] Plaw, Avery, et al. "Practice Makes Perfect?: The Changing Civilian Toll of CIA Drone Strikes in Pakistan." Perspectives on Terrorism, Dec. 2011, pp. 51–69., doi:10.21236/ada599423.

[15] Chen, Kai. "Invisible Victims of Drone Strikes in Afghanistan." Peace Review, vol. 27, no. 4, 2015, pp. 456–460., doi:10.1080/10402659.2015.1094326.

[16] Boyle, Michael J. "The Legal and Ethical Implications of Drone Warfare." Legal and Ethical Implications of Drone Warfare, 2015, pp. 1–22., doi:10.4324/9781315473451-1.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Plaw, Avery, et al. "Practice Makes Perfect?: The Changing Civilian Toll of CIA Drone Strikes in Pakistan." Perspectives on Terrorism, Dec. 2011, pp. 51–69., doi:10.21236/ada599423.

[19] Michael J. Boyle, "The Legal and Ethical Implications of Drone Warfare," The International Journal of Human Rights 19, no. 2 (February 17, 2015): 105–26, https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2014.991210; Helene Cooper, "U.S. Strikes Killed Nearly 500 Civilians in 2017, Pentagon Says," The New York Times, November 5, 2018, sec. U.S., https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/01/us/politics/pentagon-civilian-casualties.html.

[20] Maurer, Kathrin, and Andreas Immanuel Graae. "Introduction: Debating Drones: Politics, Media, and Aesthetics." Politik, 2017, http://findresearcher.sdu.dk/portal/files/143660924/Debating_Drones.pdf.

[21] "Procedures for Approving Direct Action Against Terrorist Targets Located Outside the United States and Areas of Active Hostilities." 22 May 2013, www.documentcloud.org/documents/3006440-Presidential-Policy-Guidance-May-2013-Targeted.html.

[22] Savage, Charlie, and Eric Schmitt. "Trump Poised to Drop Some Limits on Drone Strikes and Commando Raids." The New York Times, The New York Times, 21 Sept. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/09/21/us/politics/trump-drone-strikes-commando-raids-rules.html.

[23] Lewis, Michael W. "Guest Post: Pakistan's Official Withdrawal of Consent for Drone Strikes." Opinio Juris, 10 June 2013, https://opiniojuris.org/2013/06/10/guest-post-pakistans-official-withdrawal-of-consent-for-drone-strikes/.

[24] Chen, Kai. "Invisible Victims of Drone Strikes in Afghanistan." Peace Review, vol. 27, no. 4, 2015, pp. 456–460., doi:10.1080/10402659.2015.1094326.